School Board compromises publications policy

May 8, 2015

In April, 2012, the Fauquier County policy manual was restructured and updated to make it easier to navigate online. As part of this restructuring, the policy governing student publications was also revised by Frank Finn, Assistant Superintendent for Special Education and Student Services, and School Board attorney Brad King. The revisions reinstated language that had previously been rejected in the December, 2009, student publication policy.

Under the language of the 2012 policy, school principals are the “editors” of all student publications and are responsible for “approving all publications in accordance with School Board policy and his judgement and discretion.” These revisions were made without the input or knowledge of the county’s publication advisors.

“The problem with the language in the 2012 policy is that editors make all the decisions about the paper’s contents, and those editors should be the students. A principal can censor a particular article in certain circumstances, but he or she shouldn’t say what topics can or can’t be written about,” Falconer advisor Marie Miller said. “Student journalists often report on and question decisions by school administrators. A principal should not be given authority to use a vague standard like ‘discretion’ to censor student articles about his or her policies.”

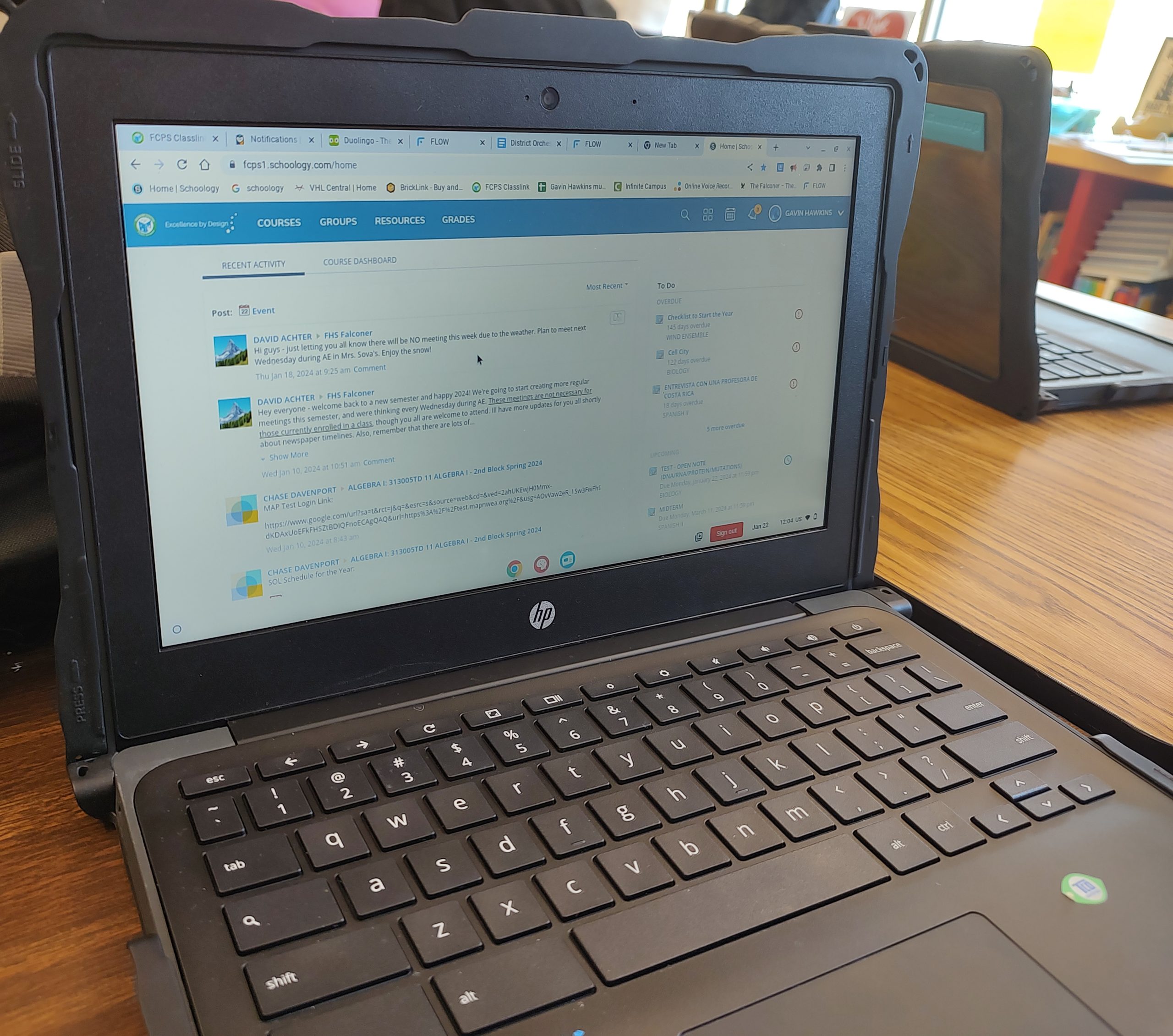

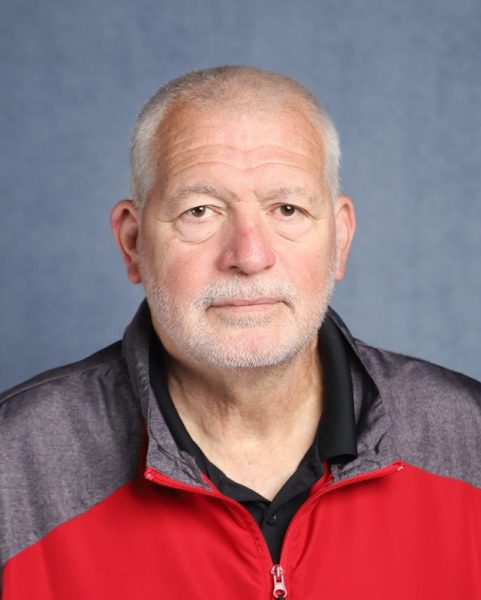

In the fall of 2009, the publications policy was revised to meet the needs of students to express their viewpoints and write about their school community under the protection of the First Amendment. This policy revision ensured that students avoided unprotected speech and operated within Supreme Court cases like Hazelwood and Tinker. During this process, input was obtained from all county publications advisors and principals. The 2012 publications policy was brought to attention during the controversy of censoring the FHS student newspaper, The Falconer. Because it was updated three years ago, Principal Clarence Burton was not involved in the revision process. However, he asserts that the 2012 revisions do not change his role of overseeing the school’s publications.

“It’s kind of like a filter system, if the faculty adviser feels there’s something that needs to be looked at,” Burton said. “I don’t see it as any change in the way we’ve gone about business in the almost three years that I’ve been here.”

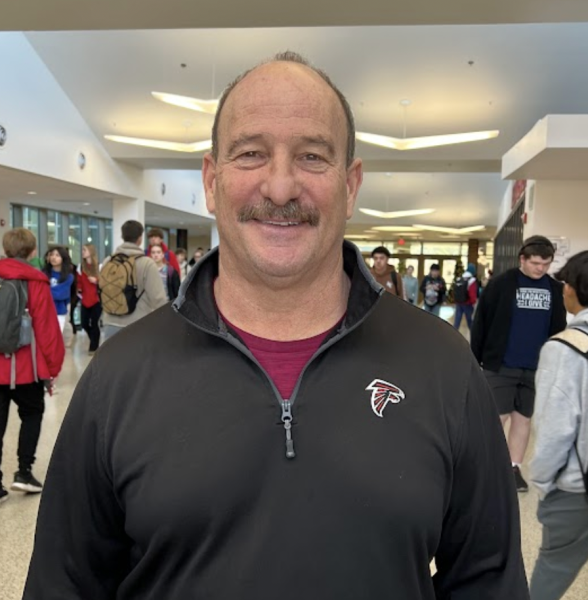

However, according to Finn, prior review is necessary under the 2012 policy. Finn said the language in the December, 2009, publications policy was too weak, because it simply stated, “The school principal is responsible for all school publications.” The principal should be given absolute authority in student publications, according to Finn.

“One of the things I’m concerned about with that language [in the December, 2009, policy] is it’s a little vague. What does that really mean?” Finn said. “What authority does that grant him? Maybe the ‘editor’ is problematic, but maybe the policy that preceded it is problematic in the other extreme.”

Finn acknowledges that principals would have to engage in prior review in order to “approve” publications under the current policy.

“I think that’s part of the problem: how practical is it that a principal can read every article independently and go through it in detail and make editorial decisions?” Finn said. “I don’t think any principal has the where-with-all or the time to do that. The principal does not want or really need to have the responsibility of editorial control of the publication because that takes away all the uniqueness of a student publication. What they do need, though, is the explicit right to make decisions.”

According to Finn, the Supreme Court’s Hazelwood case gives schools the ability to limit or censor student publications for speech that is not consistent with the school’s educational mission. Hazelwood provided the rationale for the censorship of The Falconer’s article on dabbing when the principal found the article was not appropriate for its intended audience.

“What is frustrating is that the December, 2009, policy gave principals all the authority they need under existing case law and the First Amendment to censor student publications,” Miller said. “The ‘editor’ and ‘judgment and discretion’ language was specifically rejected when policy was adopted because it invited violations of students’ First Amendment rights.”

Finn is in the process of drafting proposed changes to the 2012 policy which will be circulated to the county’s publications advisers for comment. The revisions should be in place by the beginning of the 2015 fall term.

“If the word editor attached to the principal is problematic, then what other language can we construct that gives him that explicit authority, but doesn’t have to put him in the role of editor. That’s the essence of the struggle we’re having right now,” Finn said. “From my perspective what we’re trying to ensure is that the principal has decision over student-generated publication of any sort–articles, the yearbook–when there’s a specific issue that goes against the specific mission of the educational institution.”

For now, Burton will not engage in prior review of all publications; and will only look at material that may be controversial or disruptive to a school day.

“I don’t see working much differently than I have in the past. Mrs. Miller will bring me things she expects to be controversial or that I may need to look at. As of now I don’t see myself looking at everything–that’s not going to happen,” Burton said. “[The policy] is all in interpretation. I don’t interpret it that way. If I’m told to do that [prior review], then I guess I have to, but it’s not something I want to do. I trust Mrs. Miller’s judgment.”

Superintendent David Jeck asserts the 2012 policy’s specific language makes the policy stronger and better defines the purpose of school publications.

“The 2012 policy adds more specificity, which strengthens the policy,” Jeck said. “Student newspapers are not forums for the expression of free student speech. Student newspapers are a School Board approved component of the school division’s curriculum with an ‘…. intended purpose, as a supervised learning experience for journalism students’ (quoting Hazelwood). Likewise, the School Board maintains complete control over all approved curriculum.