In July, 2009, Fauquier County adopted a student publications policy that severely compromised the First Amendment rights of student journalists by stating that the principal was the “editor” of all student publications and responsible for “approving” all publications with his “judgement and discretion.” Deeply troubled by this policy, the county publication advisers and principals worked with then superintendent Dr. Jonathan Lewis to develop a publications policy that balanced the needs of students to express their viewpoints and write about their school community with administrative concerns about acceptable speech in the public school setting. The School Board adopted this revised policy in December, 2009, and praised the process by which the compromise was reached.

In 2012, Assistant Superintendent Frank Finn and School Board Attorney Brad King “updated” the publications policy by reinstating language that again makes the principal the “editor” of all student publications and responsible for “approving all publications in accordance with School Board policy and his judgment and discretion.” The 2012 revisions were made without input from any county publications adviser. Moreover, the revised policy was not made known to any adviser until the recent controversy about the censorship of The Falconer’s article on dabbing. Setting aside concerns about the way these changes were made, the 2012 publications policy severely undercuts the journalism programs in Fauquier County.

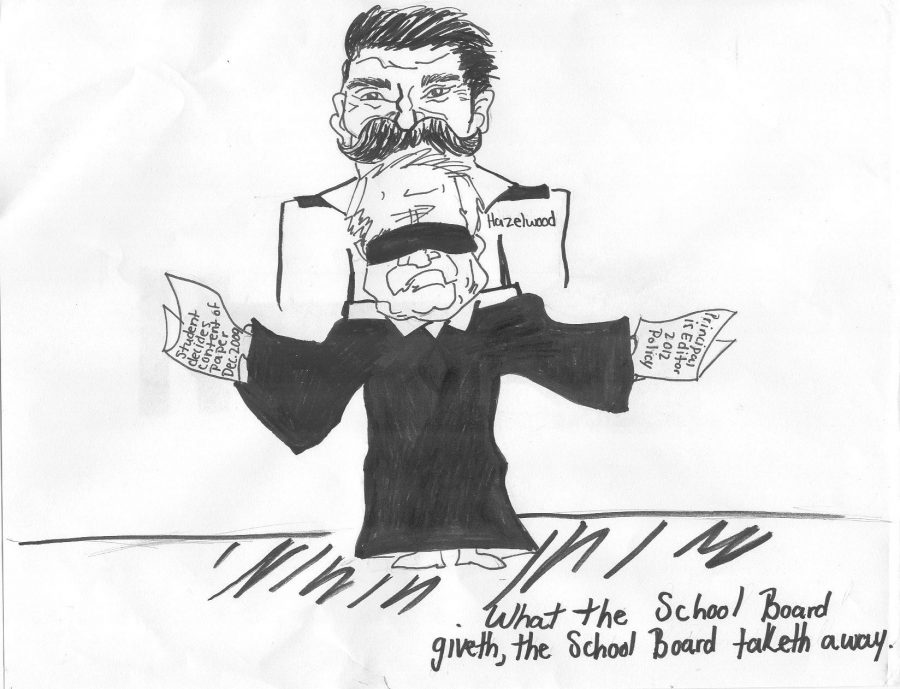

Editors are in charge of running a publication. They help develop and approve a story list and have the authority to decide what viewpoints or stories run or do not run. The language in the 2012 policy takes away the editor role from student journalists and gives it to the principal. Under the Supreme Court’s Hazelwood decision, principals can censor student speech without violating the First Amendment as long as he or she has a legitimate educational purpose. These legitimate purposes were identified in the December, 2009, policy. However, under the 2012 policy, the principal is allowed to use his “judgment and discretion” when deciding what goes in student publications. This implies that a principal could censor any viewpoint or article topic he or she does not agree with, including pieces that criticized his actions and decisions.

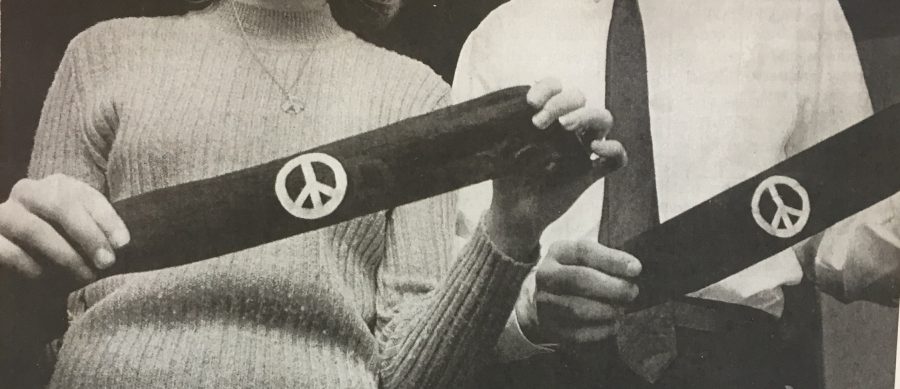

This is a conflict of interest. Student journalists have a right to and are largely responsible for covering and expressing viewpoints about decisions made by the administration. Public school principals are government officials. As government officials under the First Amendment, they are bound to not infringe upon the First Amendment rights of journalists reporting on their policies. Just because students are in a public school does not mean that their First Amendment rights do not exist, and making a principal the editor-in-chief of student publications ultimately contradicts his role as a government official.

Although Hazelwood allows prior review in certain circumstances, it does not require it. However, as Assistant Superintendent Finn made clear, the 2012 policy does – how can a principal “approve” a publication without reading it? Prior review leads to censorship. After being reviewed, the dabbing article was censored on the grounds that it was unsuitable for freshmen. Prior review creates biased articles that do not report news accurately. During discussions of the censorship of the dabbing article, it was suggested that the administration could “edit” the article to better reflect the administration’s viewpoint by removing the frank quotes that described the experiences of student users. This is not acceptable journalism in the school world any more than it is in the “real world.”

Prior review also leads to self-censorship. Now, student journalists at FHS are afraid to cover controversial topics concerning the student body, and are even avoiding using certain words, out of fear that their work will be censored by the administration. Can The Falconer write about underage drinking? Can The Falconer write about sexual activity among teens?

The student voice is crucial. It offers a perspective on student life unlike any other, and it gives a voice to the voiceless. School publications should be a forum for students to write about matters concerning their peers and matters that are important to their peers, in a respectful manner in the school community. Publications are forums to discuss student life, and students have an essential voice that deserves to be heard. Most importantly, school publications are a way to learn about and practice real journalism. This is valuable beyond words. Student publications are not, and should not be forced to be, a mouthpiece for the administration. Making material in publications up to the principal’s “judgment and discretion” violates students’ First Amendment rights. The new publication policy is unconstitutional and severely damages the human rights of student journalists.

The School Board should reinstate the carefully crafted language of the December, 2009, policy. Under this policy the administration already had sufficient authority to censor what they feel is inappropriate, as shown by the censorship of the article about dabbing. The School Board should not have policies that encourage school administrators to dictate what student journalists can or should write about.

Categories:

Publications policy requires review

May 8, 2015

Story continues below advertisement

Tags:

Donate to The Falconer

Thanks for reading The Falconer. We're happy to provide you with award-winning student journalism since 1963, free from bias, conflicts of interest, and paywalls. We're able to continue with the generous support of our local community. If you're able, please consider making a donation. Any amount is incredibly helpful and allows us to pursue new and exciting opportunities.