Lucy Parson’s Legacy Lives On

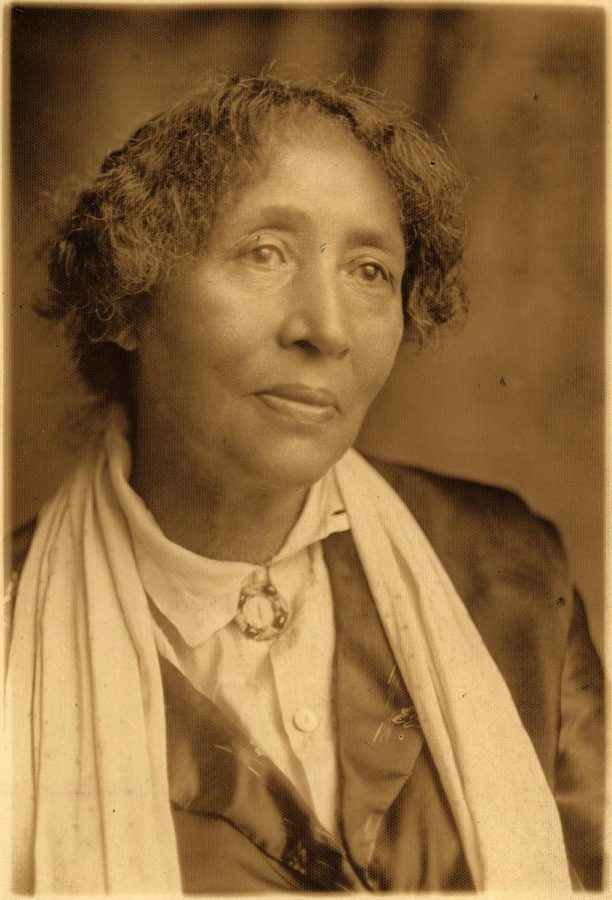

Portrait of Lucy Parsons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lucy_Parsons.1920.jpg

March is Women’s History Month, a month dedicated to the accomplishments and contributions women have made to history. The history of the labor movement in the United States is not frequently discussed, and the involvement of women in this movement is discussed even less. Lucy Parsons was an anarcho-communist revolutionary who the Chicago Police department called “more dangerous than 1,000 rioters.”

Not much is known about Parsons’ early life. She was most likely born in Virginia some time around 1851, and was born a slave to a woman named Charlotte. During Parsons’ childhood, her enslaver moved her family to Texas. After that, Charlotte and her family escaped to Waco. Throughout Parsons’ life, she usually identified as Mexican, possibly to minimize her African heritage during a time when racism against Black people was very widespread.

In 1872, Lucy Parsons married Albert Parsons, a white man who was a newspaper editor and a former Confederate soldier. They were forced to leave Texas, as Albert Parsons received death threats for registering Black voters and Texas had recently outlawed interracial marraiges. The couple then settled in Chicago in 1873, where they were introduced to the labor movement and to radical politics. After giving a speech to a crowd of more than twenty thousand people in support of striking rail workers, Albert Parsons was fired from the Chicago Times. In 1883, Lucy and Albert created an anarchist publication called The Alarm.

During May of 1886, workers throughout the country went on strike demanding a 40-hour-work week. 350,000 workers participated in the strike, with 40,000 striking in Chicago alone.

On May 3, police opened fire on a group of unarmed strikers outside a plant owned by the McCormick Harvesting Machine company, killing one worker. The next day, over 2,000 strikers marched to Haymarket square to protest the shooting. The protest started out peacefully, but turned violent when someone threw a bomb at the police officers. The police then opened fire on the strikers. After the fighting ended, seven police officers and four to eight workers lay dead. Despite the fact that the identity of the bomber was unknown– and remains unknown to this day– the police and the local authorities used the Haymarket riot as an excuse to brutally crack down on labor activists in Chicago, shutting down anarchist newspapers and raiding homes without warrent.

Although there was no evidence that they were involved in the bombing, Albert Parsons, along with seven other anarchist and socialist activists, were brought to trial for murder. Lucy Parsons was arrested, but wasn’t brought to trial because she was a woman, and authorities thought putting her on trial would decrease the chances of the eight anarchists being sentenced to death. The eight anarchists were all convicted, with five, including Albert Parsons, being sentenced to death. Lucy Parsons toured the country, campaigning against the unjust convictions of the Haymarket Eight. Despite the fact that she did help educate the public about what was happening, Albert Parsons and three other anarchists were hanged on November 11, 1887. According to PBS, Albert’s last words were, “Let the voice of the people be heard.”

After her husband became a martyr for the anarchist cause, Lucy Parsons vowed to continue fighting against injustice. In 1905, Lucy Parsons became a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World, or the IWW, a revolutionary labor union with ties to anarchism and socialism. After the Scottsboro boys, a group of young Black men, were falsely accused of raping two white women and were sentenced to death in 1931, Lucy Parsons worked with the International Labor Defence, a group affiliated with the Communist party, to fight for their release. Lucy Parsons continued her activism until she died on March 7, 1942 at the age of 91, in an accidental house fire.

Workers in the United States currently enjoy protections such as a 40 hour work week not because of the generosity of the government and the ruling class, but because people like Lucy and Albert Parsons had the courage to fight for the liberation of the working class. While their stories aren’t often discussed, their legacy lives on to this day.

Thanks for reading The Falconer. We're happy to provide you with award-winning student journalism since 1963, free from bias, conflicts of interest, and paywalls. We're able to continue with the generous support of our local community. If you're able, please consider making a donation. Any amount is incredibly helpful and allows us to pursue new and exciting opportunities.